A dotation [dɔ.ta.sjɔ̃] was a grant of revenues from territory conquered by the First French Empire. The dotations were made by Emperor Napoleon to family members, government figures and military officers as a means of securing their support. Those granted land were known as donataires. The system saw almost 6,000 donataires holding dotations worth, in theory, 30 million francs per year by the time of the Empire's collapse in 1814. The loss of revenue to the conquered states was significant; the Kingdom of Westphalia was never financially solvent under French rule because of the dotation system taking 20% of its income.

Process

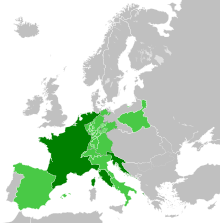

Napoleon's First French Empire acquired, by conquest, significant land in Europe. As part of Napoleon's transition into Empire, from the French First Republic, he granted various titles of nobility to his supporters. To supplement the titles and to secure support from other figures the dotation system was introduced.[1]

The revenue from part of some conquered states was assigned to the recipient, known as a donataire. The revenues were able to be passed down to the donataire's male heirs, though the recipient was supposed to have sold half of the holding within 20 years and all of it within 40 years (the intention being that the proceeds would be used to buy lands in Metropolitan France).[2][3]

The lands taken would be land belonging to feudal lords, deposed monarchs or the Catholic Church. Much of the revenue assigned came from dues previously paid to feudal lords.[4] Such a system was against the principles of the French Revolution and even against some parts of the Napoleonic Code but its value in shoring up support for Napoleon led to its widespread use.[5] English-Italian historian Stuart Woolf said of the dotation system "no better example could be given of the unresolvable contradictions between the modernizing ideals of integration of the French administrative class and the practice of exploitation that accompanied the expansion of the Empire".[5] The abolition of the feudal system would have reduced the value of the dotations significantly so any proposed reform was vigorously opposed by the donataires.[4]

The dotation system was supervised by French officials known as superintendents of the extraordinary domains.[3] The land supporting the dotations was not directly administered by the donataire but the dues were collected by French agents on their behalf.[6] Donataires had to swear a personal oath to Napoleon. Most donataires were military officers.[1]

Scale

The dotations varied significantly in value. The French government recorded dotations as one of eleven grades. The top grade consisted of 10 donataires whose dotations ranged in value from 400,000 to 1.5 million francs per year (between 1806 and 1813) including Napoleon's sisters Pauline and Elisa, senior generals Michel Ney, André Masséna, Louis-Nicolas Davout, Jean-de-Dieu Soult and Jean-Baptiste Bessières and senior ministers including Armand-Augustin-Louis de Caulaincourt. Eight donataires in the next grade held dotations worth between 200,000 and 400,000 (with a total combined revenue of 2.8 million). Other dotations were comparatively small; the lowest grade held revenues of 5,000–10,000 each and included 248 individuals with a total income of less than 2 million francs.[6]

Non-land related dotations were also known, with the donataire holding an entitlement to a portion of the loot taken by Napoleon's armies in the field.[6] In many cases revenues fell far short of their theoretical value and were the subject of complaints from a large number of donataires.[6]

As much as half of the feudally-held land seized by the French was granted in dotations. The toll on the Kingdom of Westphalia, which lost almost 20% of its revenue, meant that it failed to develop as an independent state and was never fiscally solvent.[1] Some 1,844 dotations were made from land in Italy alone. Only 27 dotations were made from the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 but these, worth 930,000 francs per year, reduced the duchy's income by a fifth. The 1809 Treaty of Schonbrunn, following the defeat of Austria, allowed a significant increase in dotations from the duchy.[7] By 1814 some 6,000 donataires held dotations worth, on paper, 30 million francs per year.[6]

End

The system collapsed with the loss of territory during the 1813-14 War of the Sixth Coalition and the dotations were effectively annulled by Napoleon's abdication.[6]

References

- ^ a b c Mikaberidze, Alexander (2020). The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History. Oxford University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-19-995106-2.

- ^ Emsley, Clive (24 October 2014). Napoleon: Conquest, Reform and Reorganisation. Routledge. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-1-317-61028-1.

- ^ a b Encyclopaedia Americana: A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics and Biography, a New Ed.; Including a Copius Collection of Original Articles in American Biography; on the Basis of the 7th Ed., of the German Conversations-lexicon. Lea & Blanchard. 1844. p. 286.

- ^ a b Sperber, Jonathan (11 June 2014). Revolutionary Europe, 1780-1850. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-317-88643-3.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze, Alexander (2020). The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-995106-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Ellis, Geoffrey (6 June 2014). Napoleon. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-317-87470-6.

- ^ Ellis, Geoffrey (6 June 2014). Napoleon. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-317-87470-6.