| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

This timeline of modern American conservatism lists important events, developments and occurrences which have significantly affected conservatism in the United States. With the decline of the conservative wing of the Democratic Party after 1960, the movement is most closely associated with the Republican Party (GOP). Economic conservatives favor less government regulation, lower taxes and weaker labor unions while social conservatives focus on moral issues and neoconservatives focus on democracy worldwide. Conservatives generally distrust the United Nations and Europe and apart from the libertarian wing favor a strong military and give enthusiastic support to Israel.[1]

Although conservatism has much older roots in American history, the modern movement began to gel in the mid-1930s when intellectuals and politicians collaborated with businessmen to oppose the liberalism of the New Deal led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, newly energized labor unions and big city Democratic machines. After World War II, that coalition gained strength from new philosophers and writers who developed an intellectual rationale for conservatism.[2]

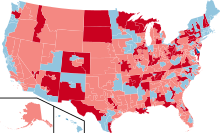

Richard Nixon's victory in the 1968 presidential election is often considered a realigning election in American politics. From 1932 to 1968, the Democratic Party was the majority party as during that time period the Democrats had won seven out of nine presidential elections and their agenda gravely affected that undertaken by the Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, but the election of 1968 reversed the situation completely. The Vietnam War split the Democratic Party. White ethnics in the North and white Southerners felt the national Democratic Party had deserted them. The white South has voted Republican at the presidential level since the 1950s and at the state and local level since the 1990s.

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan rejuvenated the conservative Republican ideology, with tax cuts, greatly increased defense spending, deregulation, a policy of rolling back communism, a greatly strengthened military and appeals to family values and conservative Judeo-Christian morality. His impact has led historians to call the 1980s the Reagan Era.[3] The Reagan model remains the conservative standard for social, economic and foreign policy issues. In recent years, social issues such as abortion, gun control and gay marriage have become important. Since 2009, the Tea Party movement has energized conservatives at the local level against the policies made by the presidency of Barack Obama, leading to Republican success in the 2010 and 2014 mid-term elections, and the 2016 election, in which Donald Trump was elected president.

YouTube Encyclopedic

-

1/5Views:3 623 1895413 0396043 716

-

The Rise of Conservatism: Crash Course US History #41

-

Modern American Conservative History

-

The History of American Conservatism

-

The History of Modern Conservatism.

-

Rise of Conservatism Simplified: Goldwater (1964) to Reagan (1989) & Beyond

Transcription

Episode 41: Rise of Conservatism Hi, I’m John Green, this is CrashCourse U.S. history and today we’re going to--Nixon?--we’re going to talk about the rise of conservatism. So Alabama, where I went to high school, is a pretty conservative state and reliably sends Republicans to Washington. Like, both of its Senators, Jeff Sessions and Richard Shelby, are Republicans. But did you know that Richard Shelby used to be a Democrat, just like basically all of Alabama’s Senators since reconstruction? And this shift from Democrat to Republican throughout the South is the result of the rise in conservative politics in the 1960s and 1970s that we are going to talk about today. And along the way, we get to put Richard Nixon’s head in a jar. Stan just informed me that we don’t actually get to put Richard Nixon’s head in a jar. It’s just a Futurama joke. And now I’m sad. So, you’ll remember from our last episode that we learned that not everyone in the 1960s was a psychedelic rock-listening, war-protesting hippie. In fact, there was a strong undercurrent of conservative thinking that ran throughout the 1960s, even among young people. And one aspect of this was the rise of free market ideology and libertarianism. Like, since the 1950s, a majority of Americans had broadly agreed that “free enterprise” was a good thing and should be encouraged both in the U.S. and abroad. Mr. Green, Mr. Green, and also in deep space where no man has gone before? No, MFTP. You’re thinking of the Starship Enterprise, not free enterprise. And anyway, Me From The Past, have you ever seen a more aggressively communist television program than “The Neutral Zone” from Star Trek: The Next Generation’s first season? I don’t think so. intro Alright so, in the 1950s a growing number of libertarians argued that unregulated capitalism and individual autonomy were the essence of American freedom. And although they were staunchly anti-communist, their real target was the regulatory state that had been created by the New Deal. You know, social security, and not being allowed to, you know, choose how many pigs you kill, etc. Other conservatives weren’t libertarians at all but moral conservatives who were okay with the rules that enforced traditional notions of family and morality. Even if that seemed like, you know, an oppressive government. For them virtue was the essence of America. But both of these strands of conservatism were very hostile toward communism and also to the idea of “big government.” And it’s worth noting that since World War I, the size and scope of the federal government had increased dramatically. And hostility toward the idea of “big government” remains the signal feature of contemporary conservatism. Although very few people actually argue for shrinking the government. Because, you know, that would be very unpopular. People like Medicare. But it was faith in the free market that infused the ideology of the most vocal young conservatives in the 1960s. They didn’t receive nearly as much press as their liberal counterparts but these young conservatives played a pivotal role in reshaping the Republican Party, especially in the election of 1964. The 1964 presidential election was important in American history precisely because it was so incredibly uncompetitive. I mean, Lyndon Johnson was carrying the torch of a wildly popular American president who had been assassinated a few months before. He was never going to lose. And indeed he didn’t. The republican candidate, Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, was demolished by LBJ. But the mere fact of Goldwater’s nomination was a huge conservative victory. I mean, he beat out liberal Republican New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. And yes, there were liberal Republicans. Goldwater demanded a harder line in the Cold War, even suggesting that nuclear war might be an option in the fight against communism. And he lambasted the New Deal liberal welfare state for destroying American initiative and individual liberty. I mean, why bother working when you could just enjoy life on the dole? I mean, unemployment insurance allowed anyone in America to become a hundredaire. But it was his stance on the Cold War that doomed his candidacy. In his acceptance speech, Goldwater famously declared, “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” Which made it really easy for Johnson to paint Goldwater as an extremist. In the famous “Daisy” advertisement, Johnson’s supporters countered Goldwater’s campaign slogan of “in your heart, you know he’s right” with “but in your guts you know he’s nuts.” So in the end, Goldwater received a paltry 27 million votes to Johnson’s 43 million, and Democrats racked up huge majorities in both houses of Congress. This hides, however, the significance of the election. Five of the six states that Goldwater carried were in the Deep South, which had been reliably democratic, known as the “Solid South,” in fact. Now, it’s too simple to say that race alone led to the shift from Democratic to the Republican party in the South because Goldwater didn’t really talk much about race. But the Democrats, especially under LBJ, became the party associated with defending civil rights and ending segregation, and that definitely played a role in white southerners’ abandoning the Democrats, as was demonstrated even more clearly in the 1968 election. The election of 1968 was a real cluster-Calhoun, I mean, there were riots and there was also the nomination of Hubert Humphrey, who was very unpopular with the anti-war movement, and also was named Hubert Humphrey, and that’s just what happened with the Democrats. But, lost in that picture was the Republican nominee, Richard Milhous Nixon, who was one of the few candidates in American history to come back and win the presidency after losing in a previous election. How’d he do it? Well, it probably wasn’t his charm, but it might have been his patience. Nixon was famous for his ability to sit and wait in poker games. It made him very successful during his tour of duty in the South Pacific. In fact, he earned the nickname “Old Iron Butt.” Plus, he was anti-communist, but didn’t talk a lot about nuking people. And the clincher was probably that he was from California, which by the late 1960s was becoming the most populous state in the nation. Nixon won the election, campaigning as the candidate of the “silent majority” of Americans who weren’t anti-war protesters, and who didn’t admire free love or the communal ideals of hippies. And who were alarmed at the rights that the Supreme Court seemed to be expanding, especially for criminals. This silent majority felt that the rights revolution had gone too far. I mean, they were concerned about the breakdown in traditional values and in law and order. Stop me if any of this sounds familiar. Nixon also promised to be tough on crime, which was coded language to whites in the south that he wouldn’t support civil rights protests. The equation of crime with African Americans has a long and sordid history in the United States, and Nixon played it up following a “Southern strategy” to further draw white Democrats who favored segregation into the Republican ranks. Now, Nixon only won 43% of the vote, but if you’ve paid attention to American history, you know that you ain’t gotta win a majority to be the president. He was denied that majority primarily by Alabama Governor George Wallace, who was running on a pro-segregation ticket and won 13% of the vote. So 56% of American voters chose candidates who were either explicitly or quietly against civil rights. Conservatives who voted for Nixon hoping he would roll back the New Deal were disappointed. I mean, in some ways the Nixon domestic agenda was just a continuation of LBJ’s Great Society. This was partly because Congress was still in the hands of Democrats, but also Nixon didn’t push for conservative programs and he didn’t veto new initiatives. Because they were popular. And he liked to be popular. So in fact, a number of big government “liberal” programs began under Nixon. I mean, the environmental movement achieved success with the enactment of the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board were created to make new regulations that would protect worker safety and make cars safer. That’s not government getting out of our lives, that’s government getting into our cars. Now, Nixon did abolish the Office of Economic Opportunity, but he also indexed social security benefits to inflation and he proposed the Family Assistance Plan that would guarantee a minimum income for all Americans. And, the Nixon years saw some of the most aggressive affirmative action in American history. LBJ had begun the process by requiring recipients of federal contracts to have specific numbers of minority employees and timetables for increasing those numbers. But Nixon expanded this with the Philadelphia plan, which required federal construction projects to have minority employees. He ended up attacking this plan after realising that it was wildly unpopular with trade unions, which had very few black members, but he had proposed it. And when Nixon had the opportunity to nominate a new Chief Justice to the Supreme Court after Earl Warren retired in 1969, his choice, Warren Burger was supposed to be a supporter of small government and conservative ideals, but, just like Nixon, he proved a disappointment in that regard. Like, in Swan v. Charlotte-Mecklenbug Board of Education, the court upheld a lower court ruling that required busing of students to achieve integration in Charlotte’s schools. And then the Burger court made it easier for minorities to sue for employment discrimination, especially with its ruling in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. This upheld affirmative action as a valid governmental interest, although it did strike down the use of strict quotas in university admissions. Now, many conservatives didn’t like these affirmative action decisions, but one case above all others had a profound effect on American politics: Roe v. Wade. Roe v. Wade established a woman’s right to have an abortion in the first trimester of a pregnancy as well as a more limited right as the pregnancy progressed. And that decision galvanized first Catholics and then Evangelical Protestants. And that ties in nicely with another strand in American conservatism that developed in the 1960s and 1970s. Let’s go to the ThoughtBubble. Many Americans felt that traditional family values were deteriorating and looked to conservative republican candidates to stop that slide. They were particularly alarmed by the continuing success of the sexual revolution, as symbolized by Roe v. Wade and the increasing availability of birth control. Statistics tend to back up the claims that traditional family values were in decline in the 1970s. Like, the number of divorces soared to over one million in 1975 exceeding the number of first time marriages. The birthrate declined with women bearing 1.7 children during their lifetimes by 1976, less than half the figure in 1957. Now, of course, many people would argue that the decline of these traditional values allowed more freedom for women and for a lot of terrible marriages to end, but that’s neither here nor there. Some conservatives also complained about the passage in 1972 of Title IX, which banned gender discrimination in higher education, but many more expressed concern about the increasing number of women in the workforce. Like, by 1980 40% of women with young children had been in the workforce, up from 20% in 1960. The backlash against increased opportunity for women is most obviously seen in the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1974, although it passed Congress easily in 1972. Opponents of the ERA, which rather innocuously declared that equality of rights under the law could not be abridged on account of sex, argued that the ERA would let men off the hook for providing for their wives and children, and that working women would lead to the further breakdown of the family. Again, all the ERA stated was that women and men would have equal rights under the laws of the United States. But, anyway, some anti-ERA supporters, like Phyllis Schlafly claimed that free enterprise was the greatest liberator of women because the purchase of new labor saving devices would offer them genuine freedom in their traditional roles of wife and mother. Essentially, the vacuum cleaner shall make you free. And those arguments were persuasive to enough people that the ERA was not ratified in the required ¾ of the United States. Thanks, ThoughtBubble. Sorry if I let my personal feelings get in the way on that one. Anyway, Nixon didn’t have much to do with the continuing sexual revolution; it would have continued without him because, you know, skoodilypooping is popular. But, he was successfully reelected in 1972, partly because his opponent was the democratic Barry Goldwater, George McGovern. McGovern only carried one state and it wasn’t even his home state. It was Massachusetts. Of course. But even though they couldn’t possibly lose, Nixon’s campaign decided to cheat. In June of 1972, people from Nixon’s campaign broke into McGovern’s campaign office, possibly to plant bugs. No, Stan, not those kinds of bugs. Yes. Those. Now, we don’t know if Nixon actually knew about the activities of the former employees of the amazingly acronym-ed CREEP, that is the Committee for the Reelection of the President. But this break in at the Watergate hotel eventually led to Nixon being the first and so far only American president to resign. What we do know is this: Nixon was really paranoid about his opponents, even the ones who appealed to 12% of American voters, especially after Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971. So, he drew up an enemies list and created a special investigative unit called the plumbers whose job was to fix toilets. No, it was to stop leaks. That makes more sense. I’m sorry, Stan, it’s just by then the toilets in the White House were over 100 years old, I figured they might need some fixing, but apparently no. Leaking. Nixon also taped all of the conversations in the Oval Office and these tapes caused a minor constitutional crisis. So, during the congressional investigation of Watergate, it became known that these tapes existed, so the special prosecutor demanded copies. Nixon refused, claiming executive privilege, and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in U.S. v. Nixon that he had to turn them over. And this is important because it means that the president is not above the law. So, what ultimately doomed Nixon was not the break in itself, but the revelations that he covered it up by authorizing hush money payments to keep the burglars silent and also instructing the FBI not to investigate the crime. In August of 1974, the House Judiciary Committee recommended that articles of impeachment be drawn up against Nixon for conspiracy and obstruction of justice. But the real crime, ultimately, was abuse of power, and there’s really no question about whether he was guilty of that. So, Nixon resigned. Aw man, I was thinking I was going to get away without a Mystery Document today. The rules here are simple. I guess the author of the Mystery Document, and lately I’m never wrong. Alright. Today I am an inquisitor. I believe hyperbole would not be fictional and would not overstate the solemnness that I feel right now. My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” Aw. I’m going to get shocked today. Is it Sam Ervin? Aw dang it! Gah! Apparently it was African American congresswoman from Texas, Barbara Jordan. Stan, that is much too hard. I think you were getting tired of me not being shocked, Stan, because it’s pretty strange to end an episode on conservatism with a quote from Barbara Jordan, whose election to Congress has to be seen as a huge victory for liberalism. But I guess it is symbolic of the very things that many conservatives found unsettling in the 1970s, including political and economic success for African Americans and women, and the legislation that helped the marginalized. I know that sounds very judgmental, but on the other hand, the federal government had become a huge part of every American’s life, maybe too huge. And certainly conservatives weren’t wrong when they said that the founding fathers of the U.S. would hardly recognize the nation that we had become by the 1970s. In fact, Watergate was followed by a Senate investigation by the Church Committee, which revealed that Nixon was hardly the first president to abuse his power. The government had spied on Americans throughout the Cold War and tried to disrupt the Civil Rights movement. And the Church Commission, Watergate, the Pentagon Papers, Vietnam all of these things revealed a government that truly was out of control and this undermined a fundamental liberal belief that government is a good institution that is supposed to solve problems and promote freedom. And for many Conservatives these scandals sent a clear signal that government couldn’t promote freedom and couldn’t solve problems and that the liberal government of the New Deal and the Great Society had to be stopped. Thanks for watching, I’ll see you next week. Woah! Crash Course is made with the help of all of these nice people and it exists because of...your support on Subbable.com. Subbable is a voluntary subscription service that allows you to support stuff you like monthly for the price of your choosing, so if you value Crash Course U.S. History and you want this kind of stuff to continue to exist so we can make educational content free, forever, for everyone, please check out Subbable. And I am slowly spinning, I’m slowly spinning, I’m slowly spinning. Thank you again for your support. I’m coming back around. I can do this. And as we say in my hometown, don’t forget to be awesome.

Chronology of events

1930s

As the nation plunges into its deepest depression ever, Republicans and conservatives fall into disfavor in 1930, 1932 and 1934, losing more and more of their seats. Liberals (mostly Democrats with a few Republicans and independents) come to power with the landslide 1932 election of liberal Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. In his first 100 days Roosevelt pushes through a series of dramatic economic programs known as the New Deal.[4]

The major metropolitan newspapers generally opposed the New Deal, as typified by William Randolph Hearst and his chain (Hearst had supported Roosevelt in 1932, but he parted ways in 1934.[5] Robert R. McCormick, owner of the Chicago Tribune, compared the New Deal to communism. He was also an America First isolationist who strongly opposed entering World War II to rescue the British Empire. McCormick also railed against the League of Nations, the World Court, and socialism.[6]

- 1934

- Opposition to New Deal policies first takes shape as the American Liberty League. Led by conservative Democrats such as Al Smith, it fades after Roosevelt's 1936 landslide and disbands in 1940.[7][8] Businessmen begin organizing their opposition especially to labor unions.[9]

- 1935

- Former President Herbert Hoover develops his critique of New Deal liberalism based on the values of liberty, limited government, and constitutionalism.[10]

- 1936

- President Roosevelt calls his opponents "conservatives" as a term of abuse, they reply that they are "true liberals".[11]

- Most publishers favor Republican moderate Alf Landon for president. In the nation's 15 largest cities the newspapers that editorially endorsed Landon represented 70% of the circulation, while Roosevelt won 69% of the actual voters.[12]

- Roosevelt carries 46 of the 48 states and liberals gain in both the House and the Senate, thanks to newly energized labor unions, city machines, and the WPA.[13] Since 1928 the GOP has lost 178 House seats, 40 Senate seats, and 19 governorships; it retains a mere 89 seats in the House and 16 in the Senate.[14]

- 1937

- Roosevelt's plan to pack the Supreme Court alienates conservative Democrats; most newspapers which supported FDR in 1936 oppose the plan, with many warning it was a prelude to dictatorship.[15]

- Conservative Republicans (nearly all from the North) and conservative Democrats (most from the South), form the Conservative Coalition and block most new liberal proposals until the 1960s.[16]

- The Conservative Manifesto (originally titled "An Address to the People of the United States") rallies the opposition to Roosevelt. It is drafted by Senators Josiah Bailey (D-NC) and Arthur H. Vandenberg (R-MI).[17]

- The liberal American Federation of Labor (AFL) and more leftist Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) labor federations are both growing and both support FDR. Their bitter feud over jurisdiction, however, produces numerous strikes, angers public opinion and weakens their political power.[18]

- 1938

- Opponents of conservatism weaken sharply. FDR's allies in the AFL and CIO battle each other; his court-packing plan is rejected; his attempt to purge the conservatives from the Democratic Party fails and strengthens them; the sharp recession of 1937–1938 discredits his argument that New Deal policies would lead to full recovery.[19]

- The Republicans make major gains in the House and Senate in the 1938 elections.[20]

- Leo Strauss (1899–1973), a refugee from Nazi Germany, teaches political philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York (1938–49) and the University of Chicago (1949–1969). He was not an activist but his ideas have been influential.[21]

- 1939

- As Republican senator from Ohio (1939–53), Robert A. Taft leads the conservative opposition to liberal policies (apart from public housing and aid to education, which he supported). Taft opposed most of the New Deal, entry into World War II, NATO, and sending troops to the Korean War. He was not so much an "isolationist" as a staunch opponent of the ever-expanding powers of the White House. The growth of this power, Taft feared, would lead to dictatorship or at least spoil American democracy, republicanism and civil virtue.[22]

1940s

- 1943

- Medical missionary Walter Judd (1898–1994) enters Congress (1943–63) and defines the conservative position on China as all-out support for the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and opposition to the Communists under Mao. Judd redoubled his support after the Nationalists in 1949 fled to Formosa (Taiwan).[23]

- The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is founded in Washington "to defend the principles and improve the institutions of American freedom and democratic capitalism—limited government, private enterprise, individual liberty and responsibility, vigilant and effective defense and foreign policies, political accountability, and open debate."[24]

- 1944

- March: Friedrich Hayek, an Austrian-born British economist, publishes The Road to Serfdom, which is widely read in America and Britain. He warns that well-intentioned government intervention in the economy is a slippery slope that will lead to tight government controls over people's lives, just as medieval serfdom had done.[25]

- The weekly magazine Human Events is founded by Frank Hanighen and Felix Morley with a significant contribution from ex-New Dealer Henry Regnery.[26][27] Ronald Reagan later says that the magazine "helped me stop being a liberal Democrat."[28]

- 1945

- Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973), having fled the Nazis, becomes professor of economics at New York University (1945–1969) where he disseminates Austrian School libertarianism.[29]

- 1946

- Milton Friedman (1912–2006) is appointed professor of economics at the University of Chicago.[30] Previously a Keynesian, Friedman moves right under the influence of his close friend George Stigler (1911–1991). He founds the market-oriented Chicago School of Economics which reshapes conservative economic theory. Stigler opposes regulation of industry as counterproductive; Friedman undermines Keynesian macroeconomics.[31] Friedman wins the Nobel Prize in 1976 and Stigler in 1982.

- November 5: Republicans score landslide victories in the House and Senate in off-year elections and set about enacting a conservative agenda in the 80th Congress.[32]

- 1947

- June: Congress passes the Taft-Hartley Act, designed by conservatives to create what they consider a proper balance between the rights of management and the rights of labor. Unions call it a slave labor law; Truman vetoes it and both houses override the veto.[33]

- 1948

- Deep South Democrats led by Strom Thurmond split from the National Democratic Party to form the pro-segregation States' Rights Democratic Party or Dixiecrat party. They are protesting support for civil rights legislation in the party platform and make Thurmond their nominee for president in the 1948 election. Nearly all return to the Democratic party in 1949.[34]

- Scholar Richard M. Weaver publishes Ideas Have Consequences, which influences intellectuals to question sophistic interpretations of literature.[35]

- June: Liberal Republican Thomas Dewey again wins the Republican nomination, to the frustration of conservatives.[36]

- November: Pundits are astonished when Dewey loses to incumbent Democrat Harry S. Truman in the presidential election.[37]

1950s

After the war, businessmen opposed to New Deal liberalism read Hayek, fight labor unions, and fund politicized think tanks such as American Enterprise Institute (founded 1943). They promote statewide right-to-work campaigns.[38]

- 1950

- The intellectual reputation of conservatism reaches a low ebb; Lionel Trilling observes that "liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition" and dismisses conservatism as a series of "irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas."[39]

- February: Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy gives a speech saying, "While I cannot take the time to name all the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring, I have here in my hand a list of 205." The speech marks the beginning of McCarthy's anti-communist pursuits.[40]

- 1951

- Political philosopher Francis Wilson in The Case for Conservatism (1951) defines conservatism as "a philosophy of social evolution, in which certain lasting values are defended within the framework of the tension of political conflict. And when given values are at stake the conservative can even become a revolutionary."[41][42]

- William F. Buckley Jr. with publisher Henry Regnery Company release God and Man at Yale to mixed reviews.

- 1952

- In securing the Republican Party presidential nomination, Dwight D. "Ike" Eisenhower leads moderate and liberal Republicans to victory over Sen. Robert A. Taft, the conservative champion.[43] Ike then wins the presidency in a landslide by denouncing the failures of the Truman Administration in terms of "Korea, Communism and Corruption."[44]

- Four major works of intellectual history that would influence conservatism are published: Daniel J. Boorstin's The Genius of American Politics, Peter Viereck's Conservatism: From John Adams to Churchill, Russell Kirk's The Conservative Mind, and Robert Nisbet's Quest for Community[45]

- Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) is founded by libertarian journalist Frank Chodorov (1887–1966) to counter the growing spread of collectivism; its original name was Intercollegiate Society of Individualists.[46]

- 1953

- President Eisenhower works closely with Senator Taft, the new GOP majority leader, on domestic issues; they differ on foreign policy.[47]

- 1955

- The National Review weekly magazine is founded by William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925–2008). The editors include representative traditionalists, Catholics, libertarians and ex-communists. The most notable were Russell Kirk, James Burnham, Frank Meyer, Willmoore Kendall, L. Brent Bozell, Jr., and Whittaker Chambers.[48]

- In The Liberal Tradition in American, Louis Hartz claims that there has never been a European-style conservative tradition in America and that the sole mainstream tradition is Lockean liberalism.[49]

- 1957

- Russian-born philosopher Ayn Rand (1905–1982) publishes her novel Atlas Shrugged; it attracts the libertarian wing of American conservatism by promoting aggressive entrepreneurship and rejecting religion and altruism. She influences even those conservative intellectuals who reject her ethical system such as Buckley and Whittaker Chambers.[50][51]

- 1958

- Vermont C. Royster (1914–1996) becomes editor of the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal (1958 to 1971). He wins two Pulitzer Prizes for his conservative interpretation of economic and political news.[52]

- Conservatives try economic populism to appeal to blue collar workers forced to join labor unions. The GOP pushes "right-to-work" laws in California and elsewhere, but the unions counter-organize for the Democrats. Conservatives try again in 2011.[53][54]

- November: In a deep economic recession the Democrats score a landslide victory, defeating many old-guard conservative Republicans. The new Congress has large Democratic majorities: 282 Democrats to 154 GOP in the House, 64 to 34 in the Senate. Nevertheless, the new Congress fails to pass any major liberal legislation as most committee chairs are Southern Democrats who support the Conservative Coalition.[55] Two Republicans score upsets in the face of the landslide—liberal Nelson Rockefeller as Governor of New York,[56] and Barry Goldwater as Senator from Arizona;[57] both become presidential prospects.

- December: Businessman Robert W. Welch, Jr. (1899–1985) and twelve others found the John Birch Society, an anti-communist advocacy group with chapters across the country. Welch uses an elaborate control system that enables him to keep a very tight rein on each chapter. Its major activities are circulating petitions and supporting the local police. It becomes a favorite target of attack from the left and is disowned by many of the prominent conservatives of the day.[58]

- 1959

- As late as 1959 William Buckley complains that conservatives were "bound together for the most part by negative response to liberalism," and that, philosophically, "there [is] no commonly-acknowledged conservative position."[59]

1960s

Liberalism made major gains after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, as Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) pushed through his liberal Great Society as well as civil rights laws. An unexpected bonanza helped conservatism in the late 1960s as liberalism came under intense attack from the New Left, especially in academe. This new element, says liberal historian Michael Kazin, worked to "topple the corrupted liberal order."[60] For the New Left "liberal" became a nasty epithet. Liberal commentator E. J. Dionne finds that, "If liberal ideology began to crumble intellectually in the 1960s it did so in part because the New Left represented a highly articulate and able wrecking crew."[61]

In support of Goldwater in 1964, Reagan delivers the TV address "A Time for Choosing", a speech which made Reagan the leader of movement conservatism | |

| Date | October 27, 1964 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 29:33 |

| Location | Los Angeles, CA, United States |

| Also known as | "The Speech" |

| Type | Televised campaign speech |

| Participants | Ronald Reagan |

| Website | Video clip, audio, transcript |

Movement conservatism emerges as grassroots activists react to liberal and New Left agendas. It develops a structure that supports Goldwater in 1964 and Ronald Reagan in 1976–80. By the late 1970s, local evangelical churches join the movement.[62][63] Liberalism faces a racial crisis nationwide. Within weeks of the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights law, "long hot summers" begin, lasting until 1970, with the worst outbreaks coming in the summer of 1967. Nearly 400 racial disorders in 298 cities saw blacks attacking shopkeepers and police, and looting stores.[64] Meanwhile, the urban crime rates shoot up. Demands for "law and order" escalate and the backlash causes disillusionment among working class whites with the liberalism of the Democratic Party.[65]

In the mid-1960s the GOP debates race and civil rights intensely. Republican liberals, led by Nelson Rockefeller, argue for a strong federal role because it was morally right and politically advantageous. Conservatives call for a more limited federal presence and discount the possibility of significant black voter support. Nixon avoids race issues in 1968.[66]

- 1960

- Conservatives are angered when GOP presidential nominee Richard Nixon strikes a deal with liberal leader Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon agrees to put all 14 of Rockefeller's demands in the party platform, including promises that the executive branch be totally reorganized and that Rockefeller's liberal policies on economic growth, medical care for the aged and civil rights be included.[67] Led by Goldwater, conservatives vow to organize at the grass roots and take control of the GOP.[68]

- Barry Goldwater publishes The Conscience of a Conservative. The book helps the Arizona Senator reignite the conservative movement which rallies behind the charismatic Arizona Senator.[69]

- Fall: Frank S. Meyer's article, "Freedom, Tradition, Conservatism", is published in Modern Age, argues that traditional conservatism and libertarianism share a common philosophical heritage. The concept comes to be known as "fusionism" and unites the two strands of thought.[70]

- September: William F. Buckley, Jr., forms a youth group called the Young Americans for Freedom; it helps Goldwater win the 1964 nomination but is otherwise ineffective and collapses in internal bickering.[71]

- November: Nixon loses a close election to liberal Democrat John F. Kennedy.[72]

- 1961

- Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) is founded by Pat Robertson; its signature program The 700 Club launches in 1966.[73]

- May: Texas elects Senator John Tower; he is the first Republican from the former Confederacy ever to win popular election and begins the growth of the GOP in that state.[74]

- 1962

- Buckley and the National Review launch denunciations of the John Birch Society; Goldwater agrees; the attack limits its influence to the conspiracy-minded.[75]

- 1963

- January: Governor of Alabama, Democrat George Wallace, electrifies the white South by proclaiming "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!" Wallace's angry populist rhetoric appeals to the poor farmers and workers who comprise a major part of the New Deal Coalition. He does well in Democratic primaries in the industrial North as well as the rural South. He exploits distrust of government, racial fear, anti-communism and a yearning for "traditional" American values.[77]

- 1964

- June: Senator Everett Dirksen (R-IL) plays a key role in passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to end segregation, but Goldwater joins Southern Democrats in voting against it.[79]

- Jul: George Wallace gives a speech condemning the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming that it would threaten individual liberty, free enterprise and private property rights and that "The liberal left-wingers have passed it. Now let them employ some pinknik social engineers in Washington, D.C., to figure out what to do with it."[80]

- July: Goldwater defeats liberal Republicans Rockefeller to win the GOP presidential nomination and launch a conservative crusade.

- July: Under attack as an "extremist," Goldwater lashes back in his speech accepting the GOP nomination:

I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue![81]

- November: In the presidential election, Goldwater is defeated in a landslide, and many GOP congressmen are defeated with him.[82]

- December: The American Conservative Union, the oldest conservative lobbying organization in the United States, is founded by William F. Buckley, Jr.[83]

- 1965

- William F. Buckley Jr. gains national attention by running for mayor of New York City on the ticket of the new Conservative Party of New York State. He loses the election but gains visibility and respectability for the cause in the aftermath of Goldwater's defeat.[84]

- 1966

- April: Socialist Norman Thomas appears on the premiere episode of Firing Line with host William F. Buckley. The program remains on the air for 33 years and is the longest running television program with the same host.[85]

- November: Republicans score major gains in the off-year elections, emphasizing issues of law and order. Liberal candidates endorsed by the AFL–CIO do poorly.[86] Ronald Reagan is elected governor of California.[87]

- 1967

- New Left students hold highly publicized rallies chanting, "Hey– Hey– LBJ– How many kids did you kill today?". Their confrontational rhetoric and efforts to disrupt the draft alienates millions of voters who move to the right.[88]

- A generational rift opens as leftist students espouse Marxism, sexual freedom, marijuana, rock music and long hair that outrages the older generation. Elite colleges and universities come under heavy pressure (but not the smaller state schools and community colleges that generally remain calm).[89]

- The American Spectator monthly political magazine is founded by Emmett Tyrrell; its name until 1977 was The Alternative: An American Spectator.[90]

- Phyllis Schlafly launches the Eagle Trust Fund, a precursor to the conservative think tank Eagle Forum.[91]

- 1968

- Liberalism collapses politically as the Democratic Party splits into five factions over issues of Vietnam, race and attacks from New Left.[92] Richard Nixon is elected president over Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace (American Independent Party), emphasizing the need for law and order.[93] The New Left denounced Humphrey as a war criminal, Nixon attacked him as the New Left's enabler—a man with "a personal attitude of indulgence and permissiveness toward the lawless."[94] Beinart observes that "with the country divided against itself, contempt for Hubert Humphrey was the one thing on which left and right could agree."[95]

- 1969

- Libertarian economists, especially Milton Friedman and Walter Oi, lead the intellectual charge against the draft. Nixon abolishes it as the Vietnam War ends in 1973.[96]

- Young Americans for Freedom splits into competing, irreconcilable factions.[97] The libertarians, influenced by Ayn Rand, split from the traditionalists and form the Society for Individual Liberty.[98]

1970s

Historians Meg Jacobs and Julian Zelizer argue that the 1970s were characterized by "a vast shift toward social and political conservatism," as well as a sharp decline in the proportion of voters who identified with liberalism.[99] Neoconservatism emerges as liberals become disenchanted with Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society welfare programs. They increasingly focus on foreign policy, especially anti-communism, and support for Israel and for democracy in the Third World.[100]

While Nixon continues to antagonize and anger liberals, many of his programs upset conservatives. His foreign policy with Henry Kissinger focuses on détente with the USSR and China, and becomes a main target of conservatives. Nixon is uninterested in tax cuts or deregulation, but he does use executive orders and presidential authority to impose price and wage controls, expand the welfare state, require Affirmative Action, grow the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, and create the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[101]

- 1970

- November: James L. Buckley is elected Senator for New York with 39% of the vote, running as a candidate for the Conservative Party of New York.[102]

- 1971

- Socialist Michael Harrington popularizes the term "neoconservative" for liberals who switch on foreign policy and domestic issues.[103][104]

- December 11: Libertarians meeting at the home of David Nolan organize the Libertarian Party which nominates John Hospers for president in 1972. John Hospers receives one electoral vote from a faithless elector.[105]

- 1972

- Richard Nixon wins a landslide reelection, carrying 49 states against anti-war liberal George McGovern. Suspicious of Democratic trickery, Nixon sends agents to bug the Democratic National Headquarters, then covers up his tracks when they are caught in the Watergate scandal.

- Phyllis Schlafly forms the "STOP (Stop Taking Our Privileges) ERA" movement; it blocks passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).[106]

- Robert L. Bartley (1937–2003) becomes editor of the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal; he retires in 2002 after writing and supervising tens of thousands of editorials taking a conservative position on economic and political issues. He is called "the most influential editorial writer" of his day.[107]

- 1973

- Traditional conservative Jesse Helms of North Carolina takes his Senate seat; he retires in 2002. As long-time chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he demands a staunchly anti-communist foreign policy that would reward America's friends abroad, and punish its enemies. His relations with the State Department are often acrimonious, and he blocks numerous presidential appointees. His National Congressional Club uses state-of-the-art direct mail operation to raise millions for conservative candidates and for Helms' own sharply contested reelections.[108]

- The American Conservative Union and Young Americans for Freedom start the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) as a "small gathering of dedicated conservatives."[109]

- The Heritage Foundation is founded by Paul Weyrich, Edwin Feulner and Joseph Coors.[110]

- May: In response to the United States Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, the National Right to Life Committee is formed, the oldest and largest anti-abortion organization in the United States.[111]

- 1974

- Robert Grant founds the American Christian Cause as an effort to institutionalize the Christian right as a politically active social movement.[112]

- January: The first March for Life attracts 20,000 supporters in Washington.[113]

- August: Conservatives, led by Goldwater, desert Nixon when the "smoking gun" is discovered that proves Nixon covered up the crimes of the Watergate scandal. Nixon resigns in disgrace, but his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger stays on in the moderately conservative administration of Gerald R. Ford.[114]

- November: Liberal Democrats attack Watergate and score major victories in the off-year elections.[115]

- 1976

- Commentary, a monthly Jewish magazine on politics, foreign policy, society and cultural issues that began as a liberal voice in the 1940s moves sharply to the right in the 1970s under editor Norman Podhoretz. It becomes an influential voice for Israel, anti-communism and neoconservatism by 1976, and supports Reagan in the 1980s.[116]

- George H. Nash publishes The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, arguing that Buckley's National Review fused together the traditional, libertarian and anti-Communist traditions to forge a conservative intellectual movement.[117]

- 1977

- Focus on the Family is founded by psychologist James Dobson.[118] The New York Times later calls Dobson "the nation's most influential evangelical leader."[119]

- The Save Our Children movement is formed by celebrity singer Anita Bryant to oppose the gay rights movement.[120]

- 1978

- Robert Grant, Paul Weyrich, Terry Dolan, Howard Phillips, and Richard Viguerie found Christian Voice, to recruit, train, and organize evangelical Christians to participate in elections. Grant later ousts the others.[121]

- June: California unleashes a tax revolt, with Proposition 13 to limit property taxes, promoted by Howard Jarvis (1903–1986), a long-time activist. The movement was backed by the United Organizations of Taxpayers, the Los Angeles Apartment Owners Association and realtors' associations.[122] Preconditions included steadily rising property taxes, "stagflation" and growing anger at government waste. California's tax revolt was followed by 30 other states.[123]

- 1979

- In reaction against liberal and presidential support for the UN's International Women's Year, conservative women meet in Houston to coordinate their grass roots work. Led by Phyllis Schlafly, they block passage of the ERA and work to nominate Ronald Reagan as the Republican candidate for president.[124]

- Beverly LaHaye and eight other women found Concerned Women for America (CWA) to oppose the Equal Rights Amendment. It later expands its scope to address socially conservative issues.[125] CWA has been described as "a key player in conservative evangelical politics" and according to CWA it is the largest women's organization in the United States.[126]

- February: Irving Kristol is featured on the cover of Esquire under the caption, "the godfather of the most powerful new political force in America – neoconservatism."[127]

- June: Jerry Falwell founds Moral Majority, marking the reentry of Fundamentalists into partisan politics.[128]

1980s

The decade is marked by the rise of the Christian right and the Reagan Revolution.[129] A priority of Reagan's administration is the rollback of Soviet communism in Latin America, Africa and worldwide.[130] Reagan bases his economic policy, dubbed "Reaganomics", on supply-side economics.[131]

- 1980

- April: Washington for Jesus marches in support of Reagan's positions on social issues as Pat Robertson brings together a theologically diverse coalition of charismatics, Pentecostals, Southern Baptists, and other evangelicals.[132]

- November: After denouncing Jimmy Carter's failed presidency, Reagan is elected president running on a "peace through strength" platform.[133] Republicans capture the Senate for the first time since 1953.[134]

- 1981

- Reagan promotes "supply side economics", arguing that tax cuts will stimulate the economy, which suffers high unemployment and high inflation (called "stagflation").[135]

- Reagan forms a coalition in Congress with conservative Democrats and passes his major tax cuts and increases in defense spending. He fails to cut welfare spending.[136]

- The Cold War heats up as Reagan pursues a rollback strategy in Latin America and Africa. He supports the anti-Communist "Contra" rebels who attempt to overthrow the pro-Communist Sandinista regime in Nicaragua.[137] Liberal Democrats in Congress try to block his moves and undercut the Contras, leading to a series of battles in the halls of Congress in which Reagan (mostly) prevails.[138] The Sandinistas are forced to hold fair elections in 1990, which they lose by 41%–55%.[139]

- 1982

- June: President Reagan tells the British Parliament that "the march of freedom and democracy will leave Marxism and Leninism on the ash heap of history"[140] and calls for a "crusade for freedom."[141]

- 1983

- March: President Reagan in a speech delivered to the National Association of Evangelicals denounces the Soviet Union (USSR) as an "Evil Empire".[142]

- The International Democrat Union, also called the Conservative International, a transnational alliance of conservative and liberal conservative political parties, is founded in London. Officers of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and Vice President George H. W. Bush are instrumental in the founding.[143]

- 1984

- November: proclaiming it's "Morning in America!" Reagan is reelected in a 49-state landslide victory over liberal Democrat Walter Mondale.[144]

- 1986

- September: Associate Justice William Rehnquist is confirmed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.[145] Reagan chooses Rehnquist in a deliberate effort to move the Court to the right, knowing he has the conservative constitutional agenda firmly in mind.[146]

- Replacing Rehnquist as Associate Justice, Antonin Scalia is confirmed by the Senate 90–0. He has been called "the creative, brilliant, and outspoken intellectual leader of the Court's conservative majority."[147]

- October: Congress enacts the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the second of the "Reagan Tax Cuts". The act simplifies the tax code, reduces the marginal income tax rate on the wealthiest Americans from 50% to 28%, and increases the marginal tax rate on the lowest-earning taxpayers from 10% to 15%.[148]

- November: the Iran Contra scandal draws national attention and threatened to derail Reagan's progress. Working with the CIA Reagan had authorized National Security Council officials to engage in a complicated sale of missiles to Iran with the goal of funding the Contras fighting Nicaragua. Blame increasingly centered on the key operative, Oliver North. However, in week-long dramatic testimony North emerges a conservative hero. North is convicted on minor counts but the conviction is reversed on appeal because he did not receive a fair trial. Reagan's reputation survives and he leaves office more popular than he began.[149]

- 1987

- June: In Berlin, President Reagan announces American terms for ending the Cold War, challenging Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to "Tear down this wall!"; Gorbachev allows the Berlin Wall to come down in November 1989, ending Soviet control over Eastern European satellites.[150]

- August: The Federal Communications Commission abolishes the Fairness Doctrine. Talk radio becomes dominated by conservative hosts.[151]

- August: Pat Robertson (b. 1930), an Evangelical minister, founds the Christian Coalition, which becomes a prominent voice in the Christian right. Robertson also telecasts news and commentary on his own network, the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN), founded in 1961. He runs poorly in the 1988 GOP presidential race and withdraws.[152]

- 1988

- August: The Rush Limbaugh Show debuts on Premiere Radio Networks and will become the highest-rated talk radio show in the United States.[153]

- November George H. W. Bush is elected president.[154]

- 1989

- November: the Berlin Wall falls as the satellite states free themselves from Soviet control. West Germany absorbs East Germany in 1990, and in late 1991 Communism collapses in Russia as the red flag is lowered for the last time. Reagan becomes a hero in Eastern Europe.[155]

1990s

Conservative think tanks 1990–97 mobilize to challenge the legitimacy of global warming as a social problem. They challenge the scientific evidence, argue that global warming will have benefits, and warn that proposed solutions would do more harm than good.[156]

- 1991

- October: Clarence Thomas, a black Republican, is confirmed as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court after controversial hearings that focus less on his strongly conservative beliefs than his relationship with one of his aides, Anita Hill, who accuses him of sexual harassment.[157]

- 1992

- November: George H. W. Bush is defeated by Bill Clinton in the presidential election. Bush had alienated much of his conservative base by breaking his 1988 campaign pledge: "Read my lips: no new taxes" He also seemed much more interested in remote foreign affairs than the domestic issues that concerned most voters.[158]

- 1994

- September: The Contract with America is released on the steps of the Capitol.[159] Designed by GOP House Whip Newt Gingrich, it had the effect of "nationalizing" the off-year election, as most Republican candidates endorsed it and used it as a template to promote a conservative agenda in economic policy. The Contract avoided divisive social issues.[160]

- November: in the Republican Revolution, Republicans take control of the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years. The Democrats lose 52 seats in the House and 8 in the Senate, giving the GOP margins of 230 to 204 and 53 to 47.[161]

- 1995

- January: Newt Gingrich becomes Speaker of the House. His "Contract with America" scores mixed results in Congress. Its main points (and their fate in Congress) were:[162]

Legislation Result Welfare reform Passed (Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996) Term limits for Congressmen Did not pass (U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton) Balanced budget amendment Did not pass Increase rights of victims of crime Passed (Taking Back Our Streets Act) Pro-family tax credits Passed (American Dream Restoration Act) Decrease United States role in the United Nations Did not pass Capital gains tax cut Passed (Job Creation and Wage Enhancement Act) Limit punitive damages on product liability Passed, but vetoed (Product Liability Fairness Act)

- September: The Weekly Standard, founded by William Kristol, Fred Barnes and John Podhoretz, publishes its first issue.[163] It is known as "a redoubt of 'conservatism'".[164]

- 1996

- September: Congress passes and Clinton signs the Defense of Marriage Act. DOMA was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2013.[165]

- October: Australian media mogul Rupert Murdoch launches Fox News Network. Its strong appeal to conservative viewers on cable television soon gives it more viewers than arch-rival Cable News Network (CNN).[166]

- 1997

- Matt Drudge launches his news website the Drudge Report.[167] His first assistant is Andrew Breitbart (1969–2012), who later becomes a prominent conservative voice on the web.[168] The Drudge Report achieves national prominence on January 17, 1998, when it publishes a story which comes to be known as the Monica Lewinsky scandal.[167]

- September: Christopher W. Ruddy starts conservative news website Newsmax. Its hourly updates provided timely ammunition to conservative talk show hosts.[169]

2000s

The terror attack on September 11, 2001, reorients the administration towards foreign policy and terrorism issues, providing an opportunity for neoconservatives to have a greater influence on foreign policy. The Bush Doctrine leads to long-term interventions in Afghanistan (2001–2021) and Iraq (2003–2011).[170]

On the domestic front Bush promises compassionate conservatism and works to improve education, address poverty nationwide, increase financial aid to poor countries and help alleviate AIDS in Africa.[171]

- 2000

- December: George W. Bush wins the 2000 presidential election after the Supreme Court halts a highly contentious recount in Florida.[172]

- 2001

- June: President Bush signed his 10-year tax cut into law; in 2000 he had promised to return the federal budget surplus through an across-the-board reduction in federal income taxes.[173]

- September: 9-11 terrorists attacks redefine the conservative role in foreign policy.[174]

- 2002

- Scott McConnell, Patrick Buchanan, and Taki Theodoracopulos found the paleoconservative magazine, The American Conservative.[175]

- 2003

- November: The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act is enacted.[176]

- 2004

- November: Conservatives mobilize to reelect President Bush; he defeats John F. Kerry.[177]

- 2005

- Bush pushes for a private dimension to Social Security —allowing workers to invest a portion of their Social Security taxes in stocks and bonds—but it goes nowhere.[178]

- 2006

- January: Samuel Alito, nominated by George W. Bush, is confirmed as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court on a party-line vote in the Senate.[179]

- November: Democrats make major gains in off-year elections, attacking the unpopular war in Iraq and the bungling of Hurricane Katrina relief.[180][181]

- 2007

- May: Christian right leader and founder of the Moral Majority, Jerry Falwell dies in his office in Lynchburg, Virginia.[182]

- Conservative talk show hosts mobilize fierce public opposition to the McCain–Kennedy immigration reform bill, which eventually fails.[183]

- 2008

- August: Little-known Alaska Governor Sarah Palin becomes the first woman on a national GOP ticket as nominee for Vice President.[184]

- November: Democrat Barack Obama defeated Republican John McCain by 53% to 46%. Barack Obama was elected and officially inaugurated as president of the United States of America on January 20, 2009. He was re-elected president in November 2012 and was sworn in for a second term on January 20, 2013. The national exit poll shows self-identified conservatives comprise 34% of the voters and support McCain 78% to 20%. Liberals comprise 22% of the voters and support Obama 89% to 10%. Moderates comprise 44% of the voters and support Obama 60% to 39%.[185]

- November: Proposition 8 which prescribes that marriage is between a man and a woman in California is passed with 52.2% of the vote.[186]

- 2009

- The Tea Party movement is founded, in part emerging from libertarian conservative Ron Paul's 2008 campaign for the Republican nomination.[187][188][189] The loosely organized conservative movement demands rigorous adherence to the Constitution, lower taxes, lower deficits, restrictions on illegal immigrants, and opposes Obama's health care proposals.[190]

- Activists Hannah Giles and James O'Keefe make sting videos compromising the integrity of Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN); ACORN soon dissolves.[191]

2010s

Numerous historians after 1990 re-examined the role of conservatism in recent American history, according it much greater importance than before.[192] One school of thought rejects the older consensus that liberalism was the dominant ethos. Instead it argues conservatism dominated American politics since the 1920s, with the brief exceptions of the New Deal era (1933–36) and the Great Society (1963–66).[193] However Historian Julian Zelizer argues that "liberalism survived the rise of conservatism."[194]

- 2010

- Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC holds that the free speech clause of the First Amendment applies to political speech during elections, making spending limits unconstitutional in certain cases. The Court majority upheld the libertarian approach to free speech, while the dissenters took an egalitarian approach.[195]

- November: in the largest GOP gain since 1938, 2010 became one of the most important elections in conservative history[196] as GOP candidates make major gains in midterm elections across the country for Congress, governorships and state legislatures. Conservative voters (self-identified) comprise 42% of the voters and support GOP House candidates 84% to 13%. Liberals comprise 20% of the voters and support Democrats 90% to 8%. Moderates comprise 38% of the voters and support the GOP 55% to 42%.[197] Republicans gain 63 seats in the House of Representatives and six seats in the U.S. Senate.

- 2012

- A central concern for conservatives in the 2012 GOP primaries was whether front-runner Mitt Romney is conservative enough. Numerous other challengers on the right rose and fell, notably Herman Cain, Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich, Rick Perry, and Michele Bachmann.[198] Romney moved sharply to the right and chose deficit hawk Representative Paul Ryan of Wisconsin as his running mate.[199] Obama, however, successfully mobilized his base and won reelection, as Democrats made small gains in the House and Senate.

- 2014

- November: Republicans win majorities in both houses of Congress, and flip several governorships in the 2014 midterm elections.

- 2016

- November: Republicans continue to hold both houses of Congress as well as take the White House. Donald Trump is elected as President of the United States.

2017

- April: Neil Gorsuch, nominated by Donald Trump, is confirmed as associate justice to the Supreme Court.

2018

- October: Brett Kavanaugh, nominated by Donald Trump, is confirmed as associate justice to the Supreme Court.

2020s

2020

- October: Amy Coney Barrett, nominated by Donald Trump, is confirmed as associate justice to the Supreme Court.

- November: Joe Biden defeats Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election, and Democrats retain control of the house and take control of the Senate.

2021

- January: The January 6 attack on the Capital occurs, which saw right-wing extremists storm the capital building in support of Donald Trump.

2022

- November: Republicans take control of the House in the midterm elections, while Democrats retain control of the Senate.

See also

- Timelines

- Timeline of Black conservatism in the United States

- Timeline of the Cold War

- Timeline of libertarian thinkers

- Timeline of United States history

Footnotes

- ^ Michael T. Thomas (2007). American policy toward Israel: the power and limits of beliefs Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Patrick Allitt (2009). The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History. Yale University Press. ch 1–6 covers the story down to 1945.

- ^ Sean Wilentz The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008. (2009); John Ehrman The Eighties: America in the Age of Reagan. (2008) pp. 3–8.

- ^ Anthony J. Badger (2009). FDR: the first hundred days. Hilland Wang. pp. 3–22, 74.

- ^ Graham J. White (1979). FDR and the Press. University of Chicago Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0226895123.

- ^ Richard Norton Smith (2003). The Colonel: The Life and Legend of Robert R. McCormick, 1880–1955. Northwestern University Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0810120396. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Rudolph Frederick (1950). "The American Liberty League, 1934–1940". American Historical Review. 56 (1): 19–33. doi:10.2307/1840619. JSTOR 1840619.

- ^ George Wolfskill (1962). The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934–1940. Houghton Mifflin. p. 249.

- ^ Kim Phillips-Fein (2010). Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal. W. W. Norton. p. 15. ISBN 978-0393337662. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Gordon Lloyd and David Davenport, The New Deal and Modern American Conservatism: A Defining Rivalry (2013) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brendon O'Connor (2004). A Political History of the American Welfare System: When Ideas Have Consequences. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 38. ISBN 978-0742526686. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Charles W. Smith Jr. (1939). Public Opinion in a Democracy. Prentice-Hall. pp. 85–86.

- ^ Sternsher, Bernard (1984). "The New Deal Party System: A Reappraisal". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 15 (1): 53–81. doi:10.2307/203594. JSTOR 203594.

- ^ Michael Kazin, eta al, eds. (2011). The Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0691152073.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jeff Shesol (2011). Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt Vs. The Supreme Court. W. W. Norton. pp. 299, 301–303. ISBN 978-0393338812. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Patterson, James T. (1966). "A Conservative Coalition Forms in Congress, 1933–1939". Journal of American History. 52 (4): 757–772. doi:10.2307/1894345. JSTOR 1894345.

- ^ John Robert, Moore (1965). "Senator Josiah W. Bailey and the "Conservative Manifesto" of 1937". Journal of Southern History. 31 (1): 21–39. doi:10.2307/2205008. JSTOR 2205008.

- ^ Walter Galenson (1960). The CIO challenge to the AFL. Harvard University Press. p. 542.

- ^ William E. Leuchtenburg (1963). Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: 1932–1940. HarperCollins. pp. 231–274.

- ^ Milton Plesur, "The Republican Congressional Comeback of 1938," Review of Politics, Oct 1962, Vol. 24 Issue 4, pp. 525–562 in JSTOR Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John P. East, "Leo Strauss and American Conservatism," Modern Age, (1977) 21:1 pp. 2–19 online Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geoffrey Matthews, "Robert A. Taft, the Constitution and American Foreign Policy, 1939–53," Journal of Contemporary History, July 1982, Vol. 17 Issue 3, pp. 507–522

- ^ Lee Edwards (1990). Missionary for Freedom: The Life and Times of Walter Judd. Paragon House. p. 210.

- ^ Murray L. Weidenbaum (2009). The competition of ideas: the world of the Washington think tanks. Transaction Publishers. p. 23.

- ^ F. A. Hayek (1944; 2nd ed. 2010). The Road to Serfdom. University of Chicago Press. 2nd ed. by Bruce Caldwell with prepublication reports on Hayek's manuscript, and forewords to earlier editions by John Chamberlain, Milton Friedman, and Hayek himself.

- ^ Robert McG. Thomas Jr. (June 23, 1996). "Henry Regnery, 84, Ground-Breaking Conservative Publisher". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Richard V. Allen (June 2, 2008). "Turning the Tide". National Review Online. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Lee Edwards (February 5, 2011). "Reagan's Newspaper". Human Events. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Israel M. Kirzner (2001). Ludwig von Mises: the man and his economics. ISI Books. p. 25.

- ^ He retired in 1977 and moved to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. Milton and Rose Friedman (1999). Two Lucky People: Memoirs. University of Chicago Press. p. 559.

- ^ Alan O. Ebenstein (2009). Milton Friedman: A Biography Palgrave Macmillan. p. 259.

- ^ Susan M. Hartmann (1971). Truman and the 80th Congress. University of Missouri Press. p. 7.

- ^ James T. Patterson (1972). Mr. Republican: a biography of Robert A. Taft. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 352–368.

- ^ Kari A. Frederickson (2000). The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968. The University of North Carolina Press. passim.

- ^ Fred D. Young (1995). Richard M. Weaver, 1910–1963: a life of the mind. University of Missouri. p. 9.

- ^ Michael Bowen (2011). The Roots of Modern Conservatism: Dewey, Taft, and the Battle for the Soul of the Republican Party. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 66.

- ^ "The Nation: Independence Day". Time. 1948-11-08. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ Kim Phillips-Fein (2009). Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal. W. W. Norton & Company. ch 2.

- ^ Russell Kirk (2001). The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot. Regnery. p. 476. ISBN 978-0895261717. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ "'Communists in Government Service', McCarthy Says". United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Charles W. Dunn; J. David Woodard (1991). American conservatism from Burke to Bush: an introduction. Madison Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-0819180698. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Francis Graham Wilson (2011). The Case for Conservatism. Transaction Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-1412842341. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ James T. Patterson Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft. (1972). ch 32–35.

- ^ William Lee Miller (2012). Two Americans: Truman, Eisenhower, and a Dangerous World. Random House Digital. p. 272. ISBN 978-0307957542. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Reba N. Sofer (2009). History, historians, and conservatism in Britain and the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 232.

- ^ Lee Edwards (2003). Educating for Liberty: The first Half-century of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute Regnery. ch 1.

- ^ Clarence E. Wunderlin (2005). Robert A. Taft: Ideas, Tradition, and Party in U.S. Foreign Policy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 191. ISBN 978-0742544901. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ John B. Judis (1990). William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives. Simon & Schuster. pp. 121–124, 152.

- ^ James T. Kloppenberg, "Review: In Retrospect: Louis Hartz's The Liberal Tradition in America," Reviews in American History Vol. 29, No. 3 (Sept 2001), pp. 460–478 in JSTOR Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burns, Jennifer (2004). "Godless Capitalism: Ayn Rand and the Conservative Movement". Modern Intellectual History. 1 (3): 359–385. doi:10.1017/S1479244304000216. S2CID 145596042.

- ^ Jennifer Burns (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford University Press. pp. 174–176.

- ^ Richard J. Tofel (2009). Restless Genius: Barney Kilgore, The Wall Street Journal, and the Invention of Modern Journalism. Macmillan. p. 157. ISBN 978-0312536749. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Kim Phillips-Fein, "'As Great an Issue as Slavery or Abolition': Economic Populism, the Conservative Movement, and the Right-to-Work Campaigns of 1958," Journal of Policy History, (Oct 2011), 23:4 pp. 491–512 online

- ^ Nelson Lichtenstein and Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, eds. (2012). The American Right and U.S. Labor: Politics, Ideology and Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. ch. 1.

- ^ Congress and the Nation: 1945–1964 (1965). Congressional Quarterly. pp. 28–34.

- ^ "People & Events: Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1908–1979". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Our Campaigns – AZ Senate Race, Nov 04, 1958". OurCampaigns.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Jonathan Schoenwald (2002). A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism. Oxford University Press. pp. 62–99.

- ^ Hyrum S. Lewis (2007). Sacralizing the Right: William F. Buckley Jr., Whittaker Chambers, Will Herberg and the Transformation of Intellectual Conservatism, 1945–1964. p. 8. ISBN 978-0549389996.

- ^ Michael Kazin (1998). The populist persuasion: an American history. Cornell University Press. p. 197.

- ^ E. J. Dionne (2004). Why Americans Hate Politics. Simon and Schuster. p. 37. ISBN 978-0743265737. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Rick Perlstein, "Thunder on the Right: The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960s," OAH Magazine of History, Oct 2006, Vol. 20 Issue 5, pp. 24–27

- ^ James A. Hijiya, "The Conservative 1960s," Journal of American Studies, Aug 2003, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp. 201–228

- ^ Michael Omi and Howard Winant (1994). Racial formation in the United States: from the 1960s to the 1990s Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. p. 196.

- ^ Michael W. Flamm (2007). Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Columbia University Press. ch. 9.

- ^ Thurber, Timothy N. (2007). "Goldwaterism Triumphant? Race and the Republican Party, 1965–1968". Journal of the Historical Society. 7 (3): 349–384. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2007.00221.x.

- ^ Theodore H. White (1961). The Making of the President 1960. HarperCollins. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-0061900600. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Laura Jane Gifford (2009). The Center Cannot Hold: The 1960 Presidential Election and the Rise of Modern Conservatism. Northern Illinois Univ Press. p. 17.

- ^ Robert Alan Goldberg (1995). Barry Goldwater. Yale University Press. pp. 138–143, 179.

- ^ John R. E. Bliese (2002). The Greening Of Conservative America. Westview Press. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Gregory L. Schneider (1998). Cadres for Conservatism: Young Americans for Freedom and the Rise of the Contemporary Right. NYU Press. pp. 154, 167, 172.

- ^ W. J. Rorabaugh (2002). Kennedy and the Promise of the Sixties. Cambridge U.P. p. 18. ISBN 978-0521816175. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ David Marley (2007). Pat Robertson: an American life. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 97.

- ^ Sean P. Cunningham (2010). Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right. University Press of Kentucky. p. 53. ISBN 978-0813125763. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ William F. Buckley, Jr., "Goldwater, the John Birch Society, and Me". Commentary (March 2008) online Archived 2012-11-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kurson, Ken (November 5, 2011). "Book Review: Daisy Petals and Mushroom Clouds". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Dan T. Carter (2000). The politics of rage: George Wallace, the origins of the new conservatism, and the transformation of American politics LSU Press. p. 12.

- ^ "'A Time for Choosing' (October 27, 1964)". Miller Center. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Robert D. Loevy (1997). The Civil Rights Act of 1964: the passage of the law that ended racial segregation. State University of New York Press. p. 359.

- ^ Wallace, George C. (July 4, 1964). The Civil Rights Movement: Fraud, Sham, and Hoax (Speech). Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ William Safire (2008). Safire's Political Dictionary. Oxford U.P. p. 229. ISBN 978-0195343342. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Rick Perlstein (2004). Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. Hill and Wang. ch. 22.

- ^ "Our History". American Conservative Union. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Jonathan Schoenwald (2002). A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism. Oxford University Press. pp. 162–189.

- ^ Laurence Zuckerman (December 18, 1999). "How 'Firing Line' Transformed the Battleground". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Draper, Alan (Winter 1989). "Labor and the 1966 Elections". Labor History. 30 (1): 76–92. doi:10.1080/00236568900890031.

- ^ Matthew Dallek (2004). The Right Moment: Ronald Reagan's First Victory and the Decisive Turning Point in American Politics. Oxford University Press. p. ix.

- ^ Steven M. Gillon (2008). The Pact: Bill Clinton, Newt Gingrich, and the Rivalry That Defined a Generation. Oxford U.P. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0199886579. Archived from the original on 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ John T. Bethell (1998). Harvard observed: an illustrated history of the university in the twentieth century. Harvard U.P. pp. 218–232. ISBN 978-0674377332.

- ^ R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr. ed. (1987). Orthodoxy: The American Spectator's 20th Anniversary Anthology. Harper & Row. ch. 1.

- ^ Ford, Lynne E. (2010). Encyclopedia of Women and American Politics. Infobase Publishing. p. 158. ISBN 978-1438110325. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould (1993). 1968: The Election That Changed America. Ivan R. Dee. pp. 7–30.

- ^ Michael Flamm, "Politics and Pragmatism: The Nixon Administration and Crime Control," White House Studies, Feb 2006, 6:2 pp. 151–62